Safety Pin, Safety Zone

/You may have recently noticed Americans wearing safety pins on their jackets and sweaters. And you wondered what this was about.

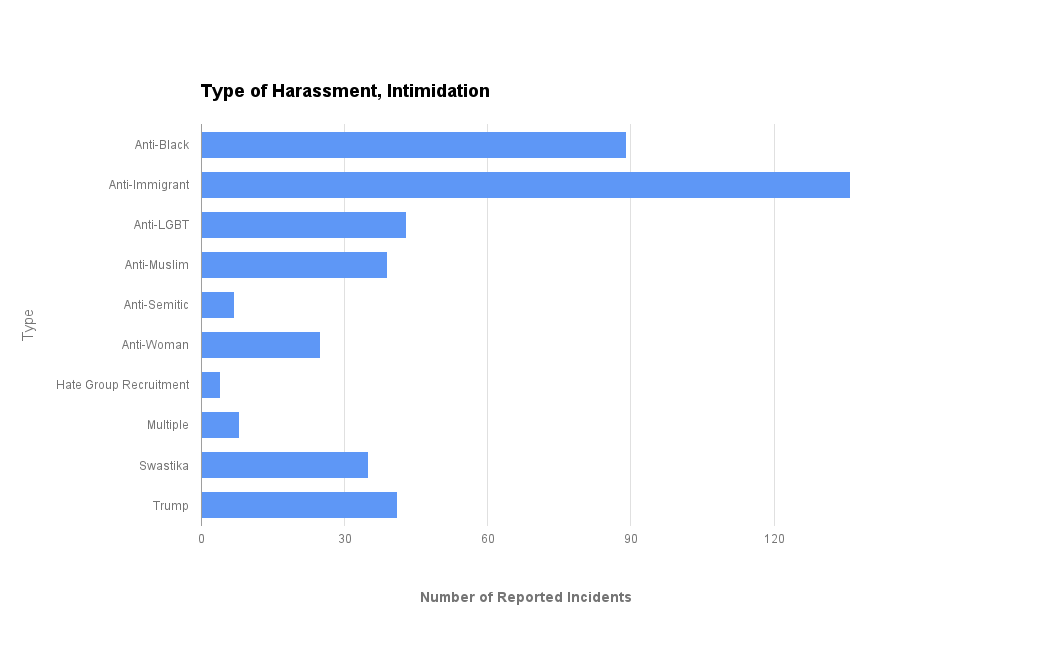

Since the highly emotional U.S. election on November 8, there has been a sharp increase in the number of hate crimes across the United States. In six days, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) tracked 437 incidents of harassment and intimidation across the country. (To be balanced, the SPLC has recorded anti-Trump incidents; that number stands at 20.)

The 437 incidents were dominated by anti-black and anti-immigrant sentiment, including:

· white teens on a bus yelling “terrorist” at a woman in a hijab (Oregon)

· white male motorist yelling “f•cking f•gg•ts” at two gay men holding hands on the street (N. Carolina)

· white woman in pickup truck yelling “White Power!” at a Latina mom with her baby at the park (Texas)

· Muslim teacher receiving note saying her headscarf “isn’t allowed anymore. Why don’t you tie it around your neck and hang yourself with it? [Signed,] America.” (Georgia)

· white male telling Filipina middle-schooler at bus stop, “You’re Asian, right? When they see your eyes, you’re going to be deported.” (Texas)

Because of this upsurge in public hate activity, organizers are asking concerned citizens to show their solidarity for people who are being targeted. This is especially important for white allies who do not normally face threats and discrimination. A safety pin indicates you are a safe person in public spaces. It indicates you will stand up against harassment.

One of my black colleagues pointed out that the wearing of the safety pin needs to go beyond the mere symbolism. It means you are preparing yourself to act as a witness in cases of public hate and intimidation. If you’re not scared away from this challenge, there are ways to get yourself ready, so you’ll know how to respond. You might employ these acts of solidarity:

· Step between the attacker and the victim.

· Lead the victim to a safe place.

· Spend time talking to the victim. (They may be very shaken.)

· Call 911. Ethnic intimidation is against the law.

· Take a cellphone video of the event, or ask bystanders to film it.

· Take a photo of the attacker’s license plate.

· Call your elected representative.

Finally, let me leave you with this well-known quote by Martin Niemöller. Niemöller was a Protestant pastor who survived eight years in Nazi concentration camps, narrowly escaping execution.

When the Nazis came for the communists, I remained silent because I was not a communist. When they locked up the social democrats, I remained silent because I was not a social democrat. When they came for the trade unionists, I did not speak out because I was not a trade unionist. When they came for the Jews, I remained silent because I wasn't a Jew. When they came for me, there was no one left to speak out.

Please summon your courage. Declare that hate will not stand in these United States.